Sharing my senior thesis

"An argument for sensuous revolution and its manifestation in our food system"

This time last year, I had just finished the months long hustle and bustle of completing my undergraduate senior thesis. As this platform now exists, I am grateful for the opportunity to share it more broadly :) Perhaps over the holidays you may stumble across leisure moments, and I’m bring this piece to your awareness for your potential consideration. I’d love to hear your thoughts/takeaways/additions. Feel free to comment, or if you feel inspired, to write something about how this might resonate with your experience. I hope you enjoy it!

Preface

Five Minute Eating Meditation By Brother Phap Linh of Plum Village

Introduction

When we look at our food system, we can understand the causes and conditions which enable and create life as we know it. Food makes us in ways I can only begin to imagine and explore, as it determines wellbeing, convening and connection with family, friends, and community, and cultural traditions. Food is also a rudimentary basis for social structures, as minority populations have been historically and presently denied the right to food sovereignty, which perpetuates systemic hierarchization. We also witness the ills of industrial food production ravaging the environment, from crises like dust bowls to greenhouse gas emissions to run-off pollutants, which adversely and disproportionately affect marginalized populations. So, from how food is grown, who food is grown by, how food is produced, where food is transported to and in what manners, how certain foods are attained and accessed, how food is prepared, consumed, and disposed, an entire life cycle is occurring on which existence is dependent.

In this food system, we witness issues such as health disparities, social injustice, and environmental injustice, which all flow within one another. When seeking to address such issues it is essential to recognize their inherent interconnectedness and root causes; otherwise, intended solutions can perpetuate the issues they aim to solve when they do not encompass full-seeing. The greatest barrier to full-seeing is disconnection with experience, which occurs when what we are experiencing is obscured by static conceptions. This inhibition of holistic understanding, when occurring through such limited perspectives, makes solving issues such as health disparities, social injustice, and environmental injustice an unintelligible pursuit. The intention of this paper is to identify the static, limited conceptions we have around ourselves and food, which can be dismantled and reformed through engagement in a sensuous revolution where we realize ourselves as embedded within a holistic circle of sustenance.

James Baldwin, a Black political thinker who considers the role static identities play in pain and social distinctions of race, sex, and class, offers us a course of action to achieve our nature. In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin asks us to take up sensuousness. He is not referring to sensual desire or craving, but rather the sensory receptivity which allows us to “respect and rejoice in the force of life” (p. 42). He goes on, advising

to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread. It will be a great day for America, incidentally, when we begin to eat bread again, instead of the blasphemous and tasteless foam rubber that we have substituted for it (p. 42).

His quote puts an image of modern society into context. However, without sensory receptivity to the bodies which ground us, which enable life and connection with it, enjoying life’s fullness is unachievable. Rather, we fabricate fragmented and nonsensical existences that are not true to our nature, where craving and desire spiral and go unsatiated. Therefore, a sensuous revolution is needed, to honor every element of our being and empower us to lead harmonious, natural, wholehearted, and fulfilled lives.

This paper will take up this idea of sensuous revolution in conjunction with the food system. The first section will synthesize the limited perspectives which arise through attachment to static pursuits of the mind and body, and how such limited perspectives can be transcended through experience-based connection, as demonstrated through Buddhism, phenomenology, and Black political thought. The second section puts these developments into the context of sensuous learning spaces, demonstrating how sensory embodiments further our holism and empower reformation across the globe. The third section offers examples of holistic embodiment as witnessed through agro-ecological movements. The paper will conclude by identifying some organizational innovations which empower marginalized groups to enliven collective agro-ecological consciousness in the food system.

Section One: Understanding Limited Perspectives

Background

Being reared and nurtured by the coastal wetland habitats of Savannah, Georgia, a sense of family and comprehensive identity swelled. My mom, taking a job as a property manager for the Girl Scouts of Historic Georgia, moved the two of us to Rose Dhu Island, a 320-acre barrier island off of Savannah’s southside, when I was seven. With a single-mother who worked full time, and without siblings or human neighbors, I quickly and easily figured out how to entertain myself in this new environment. When my mom was working and time stood still, the oak trees and spanish moss offered a canopy of protection, allowing for free and spacious imaginal explorations. They witnessed me without judgment, and safe-guarded my spirit from extrinsic expectations. Another guardian was the marsh. In spite of the stench, I was lured into its vastness and biodiversity. Periwinkle snails and hermit crabs became my favorite playmates, and marsh terrain offered limitless possibilities. In firmer areas I ran, danced, and tracked deer and raccoons, and in mud I took my baths. And how could words begin to describe the feeling of being encompassed in and embraced by such a mucky abyss? I adored being caked (or sometimes completely saturated) with grey mud, as it was a physical emblem of being from the marsh, with sulfur and sea salt as if a pheromone. I was grateful for nature as home, mother, teacher, and self, which innately stimulated and fostered sensory exploration and receptivity in a manner which was safe and wholehearted.

Through experience, I realized this aspect of self, cultivated in the freedom of nature, was not always understood in other spheres. For instance, when a palmetto bug entered my fifth grade classroom and I volunteered to take it outside, my innate, barehanded approach ensued a horror and revulsion previously foreign, and it didn’t take long to be conditioned into disliking cockroaches and the aspect of myself which cared for them. Generally, I didn’t feel that my whole self was welcome, as if I rather needed to break myself into parts and predetermine what might be well received. Away from the tall marsh grass and elder oaks, I felt I needed to assume the responsibility of protecting myself. The world didn’t feel ready for deep, sensitive love so I learned to set it aside. I didn’t realize that in being receptive to the pain and insecurities of others and taking them personally, I was creating a similarly isolated pain of my own.

I am deeply grateful to have had an outlet for (and teachers of) sensory exploration from such an early, developmental age. Still, for a long time these cultivations felt as if they were being infringed upon by the pain of dominant society, which has arisen from hierarchization within us. In this sense, hierarchization can be understood as the valuation of static conceptions over the present moment. When we relentlessly chase the desires of the mind and body and disconnect with our present realities, pain ensues as we limit our fullness. Understanding how static conceptions of the mind and body result in pain is a tool for enabling embodied holism as we develop compassion and allow our unconditional love to be felt and flourish.

Limitedness

Limits of a Static Mind

The harms of hierarchization have been expounded on in discourses of religion, phenomenology, and social justice. In That Thou Art: Aesthetic Soul/Bodies and Self Interbeing in Buddhism, Phenomenology, and Pragmatism, David Jones offers a cross-disciplinary, synthesizing account of the divisive pursuits of the mind, with an assessment of how the philosophical roots of dualism have impoverished our general wellbeing and relations with other humans, other species, nature, and the world (Jones 2020 p. 37). To reconcile this divisiveness, he later identifies other sources in the Western tradition like John Dewey, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Friedrich Nietzsche and merges them with the Buddhist concepts of interdependent-arising, the not-self, and interbeing. This article offers an opportunity to synthesize mind and soul hierarchization as well as various traditions of embodiment, which I draw on as a template for discussions of embodiment in later sections.

To begin, Jones briefly draws upon Socrates, Plato, and Descartes to exemplify the philosophical divisions and hierarchization of soul and body and counterpart of mind and body, through which the self was conceived to be “disengaged and disentangled from the web of life and lost its thread in life’s ecumenical interweaving of the world” (Jones 2020, p. 38). This has occurred as the mind/mental conceptions have been privileged in bearing the truth of life over the body and its dependence in the physical world. Rather than respecting or realizing our experiential interdependence, an a priori, conceptual, and “objective” world-view becomes revered. Unfortunately, in denying experience which offers the direct connection to the transience of life, pain ensues as static conceptions clash with change and bring identity as we know it into question. With sensory experience being denied, neglected, and deemed inferior, Jones states the body and its feelings were rendered as “shadows of some greater universal Good of Platonic form and then in the posterior form of the Christian God” (Jones 2020, p. 39). Additionally, regarding Plato’s voicing of the immortal soul, he describes an emergence of

the metaphysical Being of a higher realm over the human body and its world of stones, plants, insects, animals, and the resplendent unity of landscapes that emerged from the “interbeing” of integrally related elements (Jones 2020, p. 38).

Jones’ attribution of hierarchization to Chrisitianity and his brisk, perhaps narrow-minded movement to combat hierarchization with secular excerpts of Western philosophy felt as if leaving the idea of soul unresolved. The hierarchization Jones expounds upon is indeed an issue, and I am not sure to what degree this should be attributed to Western philosophy and Chrisitianity without considering elements of human nature, spatio-temporal moments in history, and so on. For instance, some inconsistencies may include Hegel’s embodied spirit, where ‘life-after-death’ is contingent upon this world of nature and history, residing in “our present, embodied life in so far it has been renewed and suffused with love through the anticipatory acceptance of our own death” (Houlgate 2005 p. 169). And also, there is Dostoyevsky's Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov, who’s love for God is unwaveringly inspired by the world around him, and given back to the world around him, which is beautifully encaptured as he leaves the monastery in Book VII,

Over his head was the vast vault of the sky, studded with shining, silent stars. The still-dim Milky Way was split in two from the zenith to the horizon. A cool, completely still night enfolded the earth. The white towers and the golden domes gleamed in the sapphire sky. The gorgeous autumnal flowers in the flowerbeds by the building were asleep until the morning. The silence of the earth seemed to merge with the silence of the sky and the mystery of the earth was one with the mystery of the stars… Alyosha stood and gazed for a while; then, like a blade of grass cut by a scythe, he fell to the ground. He did not know why he was hugging the earth, why he could not kiss it enough, why he longed to kiss it all… He kissed it again and again, drenching it with his tears, vowing to love it always, always. “Water the earth with the tears of your joy and love those tears,” a voice rang out in his soul. What was he weeping about? Oh, he was weeping with ecstasy, weeping, even, over those stars that shone down upon him from infinite distances, and he was “unashamed of his ecstasy”. It was as if the threads of all those innumerable worlds of God had met in his soul and his soul was vibrating from its contact with “different worlds.”... Every moment he felt clearly, almost physically, something real and indestructible, like the vault of the sky over his head, entering his soul (Dostoyevsky trans. MacAndrew 1970, pgs. 438-439).

This portrayal of the soul is so embodied and moving, utterly suffused with nature, and for this reason I feel Jones could have exercised more precision and depth in developing his associations. These prelusive examples of Hegel and Dostoyevsky demonstrate the need for deeper analysis in interpretations of the Christian soul merging and being contingent upon the earth. For, it is the Chrsitian tradition itself which reminds us of bread and wine being more than what meets the eye, where shared communion allows us to recognize the all-pervading spirit which exists around and within us. Through communion, food and drink become a medium of our physical connection to spirit, where we derive meaning from embodiment. It is precisely these embodied links which allow us to realize our interconnectedness. As Norman Wirzba states in his book Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating, “Eating joins people to each other, to other creatures and the world, and to God through forms of “natural communion” too complex to fathom” (p. 41).

Still, valuing mind over body is a byproduct of ‘objective realities’ and ‘disinterested sciences’, as phenomenologist and ecologist David Abram states, illuminating a flaw in these outlooks in his book The Spell of the Sensuous. While scientists revere an idea of emotional suppression for unbiased assessment, scientists are perhaps forgetting how they came to do their work in the first place. For, were there not unique experiences which incited feelings and passions to pursue a specific field for one reason or another? Scientists are inherently biased and subjective because our livelihoods are contingent on the experiences of embodied living (Abram pg. 33). To amend such limitations, Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully exemplifies the intersection of science and embodiment in the stories of Braiding Sweetgrass, where her experiences as a child such as family camping trips, ancestral stories, exploring nature, foraging for strawberries, and observing harmonious compliments between goldenrod and asters, inspired her to pursue formal studies in botany. When getting to college and explaining her observations which beget her wonderstruck passion for nature, she was informed by her adviser that what she was describing was not science, and perhaps she should rather consider art school. Wall Kimmerer states,

In moving from a childhood in the woods to the university I had unknowingly shifted between worldviews, from a natural history of experience, in which I knew plants as teachers and companions to whom I was linked with mutual responsibility, into the realm of science… My natural inclination was to see relationships, to seek the threads that connect the world, to join instead of divide. But science is rigorous in separating the observer from the observed, and the observed from the observer (Wall Kimmerer p. 42).

Like my experience growing up immersed in nature, Wall Kimmerer describes how the ideals of society stifled her. Being stifled, she was left feeling intrinsically dichotomized, where her passions for nature and science were treated as if mutually exclusive, but she soon realized that to divide them creates knowledge which is greatly insufficient. She had the opportunity to learn from a Navajo woman, whom, without any formal scientific training, could recite the varied intricacies of plant life and interrelationships in the ecosystem with a profundity unlike anything Wall Kimmerer had ever witnessed. She states, “I realized how shallow my understanding was. Her knowledge was so much deeper and wider and engaged all the ways of human understanding” (Wall Kimmerer p. 44). This all demonstrates how the dichotomy of mind over body and experience hinders our depth of understanding. According to Abram, through his interpretation of Edmond Husserl, the integrity and meaningfulness of science is dependent upon recognition that science and experience are rooted within the same primordial world, where quantitative and qualitative data are expressions of and guided by one another (Abram 1996 p. 43). To limit ourselves to one static aspect of being is to neglect and leave unrealized the other aspects which enable life. We must not do this if we wish to be true to ourselves and our world and fulfill our inherent interconnectedness. Such holistic thinking is essential for our food system, in order to realize all the essential parts which make up the whole.

Limits of a Static Body

When considering the limitations of the mind, it is also important to discuss the attachment which occurs on the other side of the spectrum, where sensuous craving also infringes upon holistic, embodied being. Thanissaro Bhikkhu, an American-Buddhist monk, offers understanding of this grasping through his article The Clinging to End All Clinging. He begins by unpacking the first noble truth of Buddhism which is popularly understood as the truth of suffering. Thanissaro more explicitly understands this to mean “suffering is the five clinging-aggregates” (Thanissaro Bhikku 2021, p. 1). The five aggregates--physical form, feelings, conceptions, thought fabrications, and consciousness--are constantly creating our perceptions and are inherent in the process of life, but suffering occurs when we cling to them. This clinging can take form in sensuality-clinging, view-clinging, habit-and-practice-clinging, and doctrine-of-self clinging (Thanissaro Bhikku 2021, p. 2). Doctrine-of-self-clinging is overarching as it demonstrates how attachment arises from the five aggregates as we rely on them for a sense of identity. If we rely on sensual attainment for individual identity, like material acquisition or haplessly seeking romantic satisfaction, it is easy to see how these cravings cannot be satiated through pursuing them, for the craving is what is being fed time and time again, teaching one that pleasure is found in a future which never arrives. Therefore, he states that we can reach long-term welfare and happiness through the ‘renunciation of sensuality’ (Thanissaro Bhikku 2021, p. 6). Of course, sensory experience is indivisible from our lives; rather, Thanissaro speaks to the craving and valuation of certain sensory stimuli over those which are found in the present moment. He highlights the essentiality of understanding how craving sensual experiences results in dissatisfaction. There is great depth which exists presently at our fingertips, which can entice us to not get caught in cycles of sensuous pursuit. Thanissaro offers support in abandoning clinging through observing the origin of the clinging (what causes it to arise), its dissipation, its allure, its drawbacks, and the escape from its power (p. 8). This practice can be useful when feelings arise which cause dissatisfaction with the present moment. He concludes

This is how our feeding habits come to an end: not because we force ourselves to stop eating, but because we’ve arrived at a state where there’s no need to feed: the ultimate release, free from hunger, at last (Thanissaro Bhikkhu 2021, p. 9).

His quote brings back the sentiments of the mindfulness of eating meditation by Plum Village’s Brother Phap Linh which prefaces this paper. When we eat without mindfulness, we may not remember the meal we’ve just eaten, potentially leaving us unsatisfied and craving more. Instead, the practice of mindful eating allows us to appreciate and connect with what we are consuming, being attuned to the balance which best serves our body, mind, and earth, offering satiation. As embodied beings, there cannot be abandonment of sensory receptivity- whatever we do or do not hear, feel, see, taste, and smell is perpetually creating the present moment. Allowing these experiences to flow through us without renouncing or seizing allows us to transcend limitedness, offering perhaps an ultimate freedom where we may connect and engage with the world we’re immersed within. In receiving food, through touching, smelling, tasting, and seeing, we develop appreciation for the food which sustains us and begin to cultivate an understanding for the varied conditions which enable life.

Transcending Limitedness

Buddhism and Phenomenology

In the second section of Jones’ article, That Thou Art: Aesthetic Soul/Bodies and Self Interbeing in Buddhism, Phenomenology, and Pragmatism, he exemplifies the advantages which emerge from embodied being with the world, first through the example of the Buddha. It was only when the Buddha set aside spiritual dogma for zazen, simply sitting with the elements of life as they arose without pursuing ulterior conceptions, that he became enlightened. It was through a direct experience of reality, dependent upon his place in it, that he was able to balance reality and nature with values, morality, and teachings, as these are all inherent in and inform one another. In the book Sharing Breath: Embodied Learning and Decolonization, contributor Yuk-Lin Renita Wong offers more language for understanding the embodied mindfulness of Buddhism in her chapter “Please Call Me by My True Names”. Wong describes that as the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree, he had an experience of being fully aware of what is going on in the present moment with equanimity, enabled by his groundedness (Wong 2018, pgs. 253-4). For it is precisely groundedness within the present moment which allows one to surrender the conception of desires contingent upon a past or future. This groundedness gives rise to a non-separate heart-mind, where the two merge to complete each other and offer receptivity to “the full range of experience and the fullness of life in the moment” (Wong 2018, p. 254). Further, sensory realization of life’s fluidity can be witnessed, felt, and understood while one smells, sees, hears, tastes, and feels the ever-transient symphony within and around us. Wong states, “We also begin to see that what is inside and what is outside are not separate, just as the air coming in and out of the body when we breathe is not separate from the air around us” (Wong 2018, pgs. 254-5). Therefore, the holistic experiencing of our bodies offers understandings of fullness, transience, and interbeing. Eating is undoubtedly a primary and primordial medium for cultivating such understandings, as we physically recognize our dependence on “ever-changing, dynamic entanglements with others” (Wirzba 2019, p. 12).

Jones goes on to showcase how the enlightenment of the Buddha is representative of Edmund Husserl’s idea of lebenswelt, or life-world, where knowledge comes from our participatory origin of being in and of the Earth (Jones 2020, p. 42). Through our receptivity to what we are and what is around us, knowledge and understanding can emerge. Merleau-Ponty, another phenomenologist Jones highlights, offers further depth into these processes as our body is the direct means through which we access the world and all of its life. Therefore, he holds the utmost regard for the bodily organs’ processes which enable perceiving. In Merleau-Ponty’s Eye and Mind, he begins with the quote “What I am trying to convey to you is more mysterious; it is entwined in the very roots of being, in the impalpable source of sensations” (Gasquet, Cézanne). This demonstrates his complete faith in our sensory processes, and our necessary dependence on them. Otherwise, the mysteries, or truths, of life are unfathomable and without a touchstone. When we are grounded in our senses, feeling and realizing our origination from nature, embodiment as nature, and dependence within nature, Merleau-Ponty discusses an undividedness of the sensing and the sensed (Merleau-Ponty p. 3). He gives the example of an artist and the subsequent representations which emerge. For instance, the relationship of an artist painting a mountain is a mutual dependence. The artist can only paint the mountain through receiving the mountain qualities through innate feeling and knowing of those same qualities in themself, as the mountain qualities are “both out there in the world and here at the heart of vision”(Merleau-Ponty p. 5). He is more specific in saying that “quality, light, color, depth, which are there before us, are there only because they awaken an echo in our bodies and because the body welcomes them” (Merleau-Ponty p. 4). This example is an important demonstration of our senses allowing the realization of our earthliness, and this undividedness can be further imagined within the garden. For, in order for the gardener to successfully tend to the plants, the gardener must feel a receptive tenderness within. The inevitable and just honesty of nature will reveal whether or not tenderness is present. Therefore, sensations influence the wellbeing of the gardener and the plants, a mutually contingent process. This metaphor transcends artist and mountain and gardener and plants, to showcase how giving and receiving is an inversive process.

David Abram’s Spell of the Sensuous offers thorough interpretations of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, further highlighting that the experience of life on Earth is dependent on our bodies. As the body is the very subject of experience and awareness, Abram finds Merleau-Ponty to disqualify hope for an objective philosophical position, for that would require an entity to exist aside from existence itself, which is too self-contradictory for Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenal world. However, this does bring about hope for subjective phenomenologies, making sense of our participatory lived experience occurring here and now, “rejuvenating our sense of wonder at the fathomless things, events and powers that surround us on every hand” (Abram 1996 p. 47). As experience has been demonstrated within Buddhism and phenomenology as the critical medium, it is important to discuss the utilization of connective experience within the context of social structures mankind has conceived. The field of Black political thought is exemplary of realizing and achieving such a task. These developments are critical in order to witness how social structures exacerbate food systems issues, and how experiential embodiment can offer natural solutions.

James Baldwin and The Fire Next Time

James Baldwin keenly and uniquely elucidates the fundamental nature of man. No matter how variedly our pain manifests in the world, Baldwin sees through our delusion and confusion and offers us an honest reprieve. In The Fire Next Time, his love for his audience is so profoundly moving, because he is to the audience an uncle, son, brother, friend, and lover. His all-encompassing presence transcends the pages I’m enamored with, and I understand why his perceiving gaze graces the cover of this copy, making him all the more concrete. Through Baldwin’s cultivation of such relationality, the reader can personally feel his words kindly dissolving their limited identities contingent upon separation, leaving in its trace a previously ‘illegitimate’ richness. This can be understood with Baldwin’s dialeticity, where two opposites are synthesized as one. This is a profound beauty of Baldwin as he simultaneously offers language for uniqueness and oneness. His dialectical thinking gives readers the understanding for transcending limited, lonely individualism through sensuous receptivity for experience, facilitating solidarity and collective-oriented action.

The Fire Next Time begins with a letter Baldwin has written to his nephew, a letter of compassion and resilience, of clear seeing. He explains to his nephew James,

Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one’s sense of one’s own reality. Well, the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar: and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations. . . . [B]y a terrible law, a terrible paradox, those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them safe are losing their grasp of reality. But these men are your brothers—your lost, younger brothers… And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. (Baldwin, 1963 pgs. 9-10)

We see that with static conceptions, white Americans have created an idea of life informed by thought sans experience. Identification with and attachment to static ideas of life manifest as pain as our realities assuredly undermine them. Due to our escapism from and fear of life, false identities have been constructed which are contingent on hierarchization. Therefore, when social hierarchization naturally proves to be fabricated, these false identities are completely shaken. In the previous excerpt, as the Black man inherently moves out of the identity prescribed upon him by the white man, the ‘reality’ or identity of the white man is challenged. Baldwin completes this dialectic process through the idealization of the two opposites as brothers, as being the same while simultaneously different. Most importantly, he notes that sublation of the two opposites as one is only possible when the reality of our experiences is embraced, and active reformation is occurring for holistic embrace to be accepted among all.

Regarding the individualist pain of white America, Baldwin continues to develop the dialectical dependence.

The white man’s unadmitted—and apparently, to him, unspeakable—private fears and longings are projected onto the Negro. The only way he can be released from the Negro’s tyrannical power over him is to consent, in effect, to become black himself, to become a part of that suffering and dancing country that he now watches wistfully from the heights of his lonely power and, armed with spiritual traveller’s checks, visits surreptitiously after dark. (Baldwin pgs. 95-96)

In this case, the white man, to attain freedom, must overcome his complete dependence on the Black man, which is the power the Black man has over him. This again occurs through sublation of the two races as a whole, where the white man must surrender to Blackness. This excerpt completes the dialectical picture within The Fire Next Time, as identities of white supremacy and Black inferiority must fall for freedom. Witnessing this, it’s essential to highlight how this awakening can occur. In two sentences, Baldwin determines the root of white pain and anguish as our lonely individualism, and that to be free from our mistaken loneliness, we must suffer and dance together. We must feel and surrender to our pain as one, and only then may we be released from the tyranny of the limited, lonely self.

Because of the previously portrayed dialectical dilemma, America’s ills are of extreme complexity. For scholar Addison Gayle, white America’s awakening seems improbable. He states

The problem, then, for the Negro intellectual is to confront the dialectic in The Fire Next Time, and perhaps, in so doing, he will realize that the American dilemma cannot be solved by postualting a black redeemer, who in all respects, will probably turn out, under close scrutinization, to be as helpless-if not fanatical- as the white one (Gayle 1967 p. 16).

This perspective further highlights how liberation is a mutually dependent process. If one of the opposites is not willing to transcend their limitedness, the dialectic will go unrealized. Knowing this, Baldwin concludes The Fire Next Time with the following:

Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we- and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others- do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time! (Baldwin pgs. 105-106)

Whether or not America can be redeemed, Baldwin calls us to ardently, lovingly, and unwaveringly influence and ignite embodied consciousness in others, and assume redemption is in our power. It is our moral duty to fight for what is right, and if we do not, the certain doom of society is rapidly approaching.

Our food system offers the explicit intersection between nature and social structures, where embodied consciousness is eagerly begging to be fulfilled. Consequently, in order to ignite embodied consciousness within and around us, sensuous spaces, where sensuousness is practiced communally, are essential to enable deep love for our selves, communities, and world. Without sensuousness, the means through which we cultivate our unconditional love, pain reverberates through our entire world and every direct experience whether we hold awareness of it or not. When we embrace a collective sensuousness, we do not passively hope for universal healing and love as an abstract, but we take them up and carry them in our bodies. We step forward to provoke the social change on which we are all dependent.

Section Two: Sensuousness as Praxis

Introduction to Sensuous Praxis

Food is the thread between nature and humans, where differentiation between the two occurs because of social hierarchization we have developed and ingrained in our societies. When food falls victim to social hierarchization and concurrent structures, harm results for all, diversely and disproportionately, and health, social, and environmental ills emerge. As sensuous embodiment offers the realization of nature and human mutually dependent, we can work to reform social structures for wellbeing to prevail. As Norman Wirzba states, “It is an organic, living whole that is healthy and sustainable because the success of each member presumes and promotes the well-being of each other member” (Wirzba 2019, p. 67).

To explore how this can occur, sensuous embodiment and exchange as conditional for social reformation is the premise of Valerie Kinloch and Carlotta Penn’s chapter titled “Blackness, Love, and Sensuousness as Praxis”. In highlighting sensory receptivity and deep feeling as agents of strength and change, their chapter lovingly demonstrates the interrelation of embodiment and political reform. They identify ideas of sensuousness inherent in activists and scholars like James Baldwin, June Jordan, Martin Luther King Jr., bell hooks, Mary McLeod Bethune, Angela Davis, and Audre Lorde to bring an apparent consensus to the forefront. Kinloch and Penn contend that stimulating and connecting with our senses begets “an unwavering commitment to human life, human living, and human loving”, as we live with intention and love with presence ( p. 86). This is a profound and true love, through which we garner an awareness of who we are in relation to the world of life, of living beings, around us. The authors go on to bring to light the large implications of this feeling and knowing of our immersive identities, where we learn to “deeply listen to, care about, stand alongside, and forge coalitions with others in the pursuit of justice and in the ongoing process of being and becoming more fully human” (Kinloch and Penn p. 86). This is a process of uncovering our wholeness, where mutualism is evidenced as we simultaneously foster love for ourselves and others.

It is important to mention the historical and societal infringements upon sensuous being, especially for disenfranchised people. This can be witnessed through both the reducement to and revocation of sensuousness. With sensuous reduction, marginalized groups have been victim to prejudices of a strict embodiment. In The Fire Next Time, Baldwin uses the term sensual to intentionally empower and invigorate the term as an action-oriented pursuit toward loving, respecting, rejoicing, etc., and to reject a limited sexualization which dehumanizes social groups (Kinloch and Penn p. 86) . Sensuous revocation, taking away the freedom of individuals to their bodies, whether physically or socially, has/can/will manifest in ways that are especially hostile, dangerous, and fatal to those facing oppression. For instance, we can envision this issue through Toni Morrison’s Beloved, where when the warm weather came, Baby Suggs “took her great heart to the Clearing” (p. 87), followed by all the Black men, women, and children who could make it. Protected by the depth of the woods, Baby Suggs called the children to laugh, making the forest ring, the men to dance, making groundlife shudder under their feet, and the women to cry for the living and the dead, which they did with uncovered eyes. These roles were switched so that they could all embody and share in these states of being. Once this practice was carried out she left them with this message,

In this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh. They despise it. They don't love your eyes; they'd just as soon pick em out. No more do they love the skin on your back. Yonder they flay it. And O my people they do not love your hands. Those they only use, tie, bind, chop off and leave empty. Love your hands! Love them. Raise them up and kiss them. Touch others with them, pat them together, stroke them on your face 'cause they don't love that either. You got to love it, you! And no, they ain't in love with your mouth. Yonder, out there, they will see it broken and break it again. What you say out of it they will not heed. What you scream from it they do not hear. What you put into it to nourish your body they will snatch away and give you leavins instead. No, they don't love your mouth. You got to love it. This is flesh I'm talking about here. Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms I'm telling you. And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they'd just as soon slop for hogs, you got to love them. The dark, dark liver--love it, love it and the beat and beating heart, love that too. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts, hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize. Saying no more, she stood up then and danced with her twisted hip the rest of what her heart had to say while the others opened their mouths and gave her the music. Long notes held until the four-part harmony was perfect enough for their deeply loved flesh. (Morrison 1987, pgs. 88-89).

Through this love-infused text, we can witness the personal and collective pain and numbness that arises when human beings are denied freedom, belonging, and wholeness. Nevertheless, Baby Suggs helps her community to cultivate a sanctuary, to explore, embody, and surrender to unconditional love, as she identifies the heart as the most essential element of life. Kinloch and Penn give the following explanation which provides additional clarity for sensuous action among marginalized groups:

Sensuousness—the use of all of our senses to breath life into otherwise unbearable situations, the capacity to engage in sense-making in connection with lived experiences, and the ability to love as a conscious, purposeful, and transformative act—becomes ever so important in cultivating, maintaining, and sustaining Black life and Black (self and collective) love (Kinloch and Penn p. 88).

Therefore, we see that safe, sensuous spaces are essential for marginalized groups in cultivating love which has been conditioned against. While this is a beautiful sanctuary, the fruits are still challenged and determined by the degree to which our collective world is sensuous. Until presiding, inequitable mindsets and structures are dismantled, the health, social, and environmental ills we are experiencing will continue to proliferate.

Invoking Change in Sensuous Spaces

Sensuous life force is what invigorates movements toward freedom. Black thinkers like Baldwin did not discuss sensuousness as an abstract, intellectual pondering of how to attain freedom; it is rather the embodied method through which holistic freedom can be attained. Instead of a disconnect between knowledge and practice, they are seen to actively engage one another. This holistic engagement (physically, intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, etc.) allows for a full awareness of who we are in relation to the world around us, and how our uniqueness strengthens and is strengthened by coalitions (Kinloch and Penn 2019, p. 86). Sensuous embodiment offers the intersection of the intricacies of life as we holistically interpret and make sense of our realities. Therefore, as sensuousness evokes feelings of our holism, this precipitates the critical action and reaction necessitating social change (Kinloch and Penn 2019, p. 89).

To invoke social change, sensuous spaces must be deliberately fostered. Kinloch and Penn highlight how bell hooks takes up sensuousness in the realm of education, encouraging educators not to succumb to dominant curricula which splits the mind and body, leaving beings unfulfilled. Rather, hooks wishes for us to be wholehearted in the classroom, where all of our elements of being are encouraged to be present and have outlets for expression. As this enables us to give and receive love, hooks believes critical thinking, joy, and meaningful relationships will thrive (Kinloch and Penn p. 93). I know this to be true as after 16 years of schooling, I have finally been privy to such an educational experience.

In the summer of 2021, I was selected to attend a three-week retreat on interbeing through the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. This retreat was hosted by Kirstin and William Edelglass, Larkspur Morton, and Moon Clemetson, who among them embody roles such as parents, activists, community members, holistic educators, nature stewards, scholars, scientists, therapists, artists, performers, and so much more. The August retreat they fostered included morning meditations, mindfulness-in-nature activities (like forest-bathing, contact improv, and guided tree-hugging), working meditations (gardening, cooking, wood-splitting, and trail-building), seminars (on topics like social justice, non-violent communication, living systems theory, permaculture, Buddhist poetry, and climate grief, just to name a few), and council practice (more on this later). It was incredible to feel how these practices allowed for holistic expression and fulfillment. From the beginning, our dependence on community was put into practice, as we each had essential roles to carry out on a daily basis, like cooking breakfast and dinner, cleaning the kitchen, composting humanure, recycling, and so on. When a task went unexecuted, which rarely occurred, there was a felt reverberation among the group. This allowed us to surrender into reliance and foster trust. Another outlet for this was our council practice which had been adopted from The Ojai Foundation. Almost every other evening, we would gather for council and be reminded of the practices’ six intentions, to listen from the heart, speak from the heart, be spontaneous (to not pre-determine what to say while others are speaking in order to honor what needs to be said at the present moment), speak with essence (not too short or too long), keep confidentiality, and speak with kindness for self, community, and the greater good. With this in heart and mind, we sat around campfires and under meteor showers responding to prompts that enveloped us in deep feeling. It was unfathomably relieving to share feelings of grief, fear, joy, anger, sadness, contentment, etc. and connect as a community. Finally, many of our practices were based in Joanna Macy’s The Work That Reconnects which, put simply, offers embodied, emotional, and connective practice in relation to nature and our climate crises. Some practices we carried out included the Elm Dance, the Truth Mandala, and the Living Systems Game, but the most memorable for me was by far the Milling, which was a practice for realizing the pain we hold for our world. This particular morning, we gathered in a clearing to begin a previously foreign practice. As we were waiting for a group member to arrive, I laid down on the grass and closed my eyes to feel the sun's warm rays enliven my body. After a few minutes, recognizing that we were still waiting and I hadn’t heard anything, I opened my eyes to ensure it wasn’t me holding up the group. Instead, I found everyone else lying in the grass just like me, soaking up the sun’s rays like basking sea turtles on summer sand. I closed my eyes to fully commemorate this feeling of collective embodiment. Shortly after, we began the practice while keeping our positions. Kirstin informed us that the intention of the milling practice was to honor our pain for the world, and therefore she caringly recited to us various conditions and events which afflict harm onto the natural world, jeopardizing the livelihood and wellbeing of all. While emotional responses were bubbling up within me, I heard the sound of tears being suppressed to the left of me. I briefly deliberated on what I should or shouldn’t do in this moment, whether to console them and how to go about doing so or if that might make them embarrassed or uncomfortable, before I opted to abandon rationality to act on intuition. I reached over and held their hand in mine, and as they reciprocated my grasp, tears rolled off my face to nourish the grass as well, tears which epitomized sentiments of pain, empathy, love, fear, solidarity, and relief. After a few moments, we were instructed to stand for the subsequent portion of this practice, and I felt some embarrassment arise as I was crying rather heavily at that point. I felt an urge to go off on my own to compose myself, but the activity was going on and I wasn’t about to miss it. I carried on with my grief, and quickly realized that it was okay to be crying among others. In fact, it was the intention of the practice to honor whatever feelings emerged, and with this sense of belonging I felt empowered. Tears unashamedly poured down my face as I looked into the eyes of others, feeling the beauty of their lives, their uniqueness and right to wholeness. Through honoring pain, I felt freedom, and I am deeply grateful for this experience of a communal emotional liberation.

In seminar settings, I was surprised to feel a change in my personal presence, influenced by the previously described practices. For our seminars, we were taught by our faculty, guest speakers, and fellow retreatants. Before coming to the retreat, we were assigned topics, a partner, and a faculty member in order to develop a seminar. I felt nervous for this aspect of retreat as I’ve been in student settings the majority of my life, and based on these experiences I had at times determined myself to be quiet, non-contributive, and unintelligent. While I could recognize a clear passion within myself, this devastatingly didn’t seem to translate into many spheres of student life. If it did, sharing it with others seemed daunting and unspeakable. I remember a time when my roommate was overhearing an online lecture class I was in last year, where the professor was asking questions to which few were responding. Knowing I was very passionate about the topic being discussed, she asked me why I wasn’t contributing more and I simply shrugged my shoulders. I was feeling scared that in having determined a static identity of myself as quiet/unintelligent/etc., these qualities could potentially be made aware to my classmates and professor. This all comes in great contrast to what I was experiencing on retreat. Touching my environment, trusting my classmates, and experiencing a full range of sensations and emotions in a learning environment completely transformed what I thought I was capable of in a learning space. I no longer had heart palpitations and raging doubt when I raised my hand or was speaking to the group. I was excited to contribute to conversations as I recognized the unique and indispensable perspectives which we each brought to the circle, and I felt smart and valuable. This goes to show how understanding and trust among a community can be fostered through embodiment. Honoring our sensuous experiences inspires confidence and a sense of belonging. Physical and emotional connection must be encouraged, otherwise we are leaving people with distorted perceptions of themselves as learners and as integral parts of our interconnected world.

Kinloch and Penn state that the materialization of love, passion, and critical reflection in learning settings occurs through deep care for others and ourselves (p. 93). Further, bell hooks insists that learning spaces should be a place where

… we have the opportunity to labor for freedom, to demand of ourselves and our comrades, an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries, to transgress (Kinloch and Penn 2018, p. 94).

Holding this in frame, one can clearly see how holistic engagement in learning settings can spark collective connection and as a result, action. In the food system, this process of sensuous spaces betting action is witnessed, from where agro-ecological grassroots coalitions emerge from sensuous sharing, in pursuit of justice, sovereignty, and systemic reformation. Holistic sensuous engagement is our opportunity to face the challenges present within the food system, and succeed.

Section Three: Sensuous Praxis in Agroecology

Introduction to Agroecology

Land and food are arguably the world’s most basic means of connection. According to the previous sections, if disconnection and limitedness are our world's ills, food and land can offer regenerative healing, putting us in embodied contact with family, friends, neighbors, non-human beings, and nature. This cause for connectivity can be taken up within agroecology, as the field itself offers a cohesive consideration of agriculture within the context of the greater environment, as it is rooted in scientific disciplines, agricultural practices, and political and social movements (Wezel et al 2009). These agroecological lenses are essential in considering how food production is grounded in and dependent on all life systems. Therefore, in order to enliven agro-ecological consciousness, marginalized groups must be empowered to share and enact their wisdom to restore balance to our world and food system. In Michel Pimbert’s chapter “Democratizing Knowledge and Ways of Knowing for Food Sovereignty, Agroecology, and Biocultural Diversity”, he offers an extensive synthesis of this necessity. To begin he states,

counter-hegemonic practices by peasant networks, indigenous peoples and social movements seek to reframe food, agriculture, biocultural landscapes and the ‘good life’ in terms of a larger vision based on radical pluralism and democracy, personal dignity and conviviality, autonomy and reciprocity and other principles that affirm the right to self-determination and justice... Making these other worlds possible requires the construction of radically different knowledge from that offered today by mainstream universities, policy think tanks and research institutes (Pimbert 2017, p. 261).

He demonstrates the need for players in the food system, and broader society, to complete the picture in order for the reformation we are craving to occur; we must invite democratic and holistic knowledge into action. Pimbert details that democratic knowledge recognizes the various kinds of knowledge which exist (experiential, local, tacit, feminine, scientific, etc.) , the various mediums through which it is represented (text, visuals, numbers, stories, meditation, etc.), and the understanding that knowledge is a powerful tool in taking action for a fairer and healthier world (Pimbert 2017, pgs. 269-270). As the knowledge of marginalized groups has been stifled and excluded, we are faced with the dire need to amplify, listen, and receive what has been referred to as subaltern-knowledge (Pimbert p. 269). For marginalized forms of knowledge to coalesce into empowered action, he discusses the role education spaces can play in cultivating critical consciousness inspired by experiential knowledge and place-based learning. These spaces of learning exchange can invigorate the constituents of grassroots movements to employ conscious understanding of their realities, to identify the power structures at play in their lives, and to collectively transform these structures in their communities and wider society (p. 272). bell hooks helps to pin-point the inexplicit force of these shared learning spaces, as feelings such as “spirit, struggle, solidarity and love which often motivate progressive social change and transformation” (Pimbert 2017, p. 272). As demonstrated in the previous section, these feelings emanate from connecting with our experiences and finding value within them. Therefore, sensory receptivity is the enkindling spark of agro-ecological connection and mobilization. In other words, the first step must be enabling and empowering feeling, otherwise we cannot understand how to move forward. To enable this sensory receptivity, peasant farmers and other citizens must “rely on their senses (smell, sight, taste, touch, hearing...) to perceive and interpret phenomena” (Pimbert 2017, p. 274). As sensory receptivity to experience is empowered through collaborative spaces,

careful observations and inclusive conversations help map, analyze, understand, and respond to complex and ever-changing natural and social phenomena in place-specific situations (Pimbert 2017, p. 274).

The basis of the knowledge which emerges from these spaces is indeed the sensuous and sensitive qualities of humans and their embodied, intimate relations with the environment (Pimbert 2017). This full engagement is a practice of connection-making, where realizing the reciprocal processes of the Earth entices a holistic, systems-thinking worldview critical to agroecology, and more fully, all of life’s systems. This is because, according to Pimbert, empowering collective, observational inquiry

enhances people’s awareness and understanding that they are part of a social and ecological order, and are ‘radically interconnected with all other beings, not bounded individuals experiencing the world in isolation. Thus, an attitude of inquiry seeks active and increasing participation with the human and more-than-human world’ (Marshall and Reason, 2007). (Pimbert 2017, p. 277).

When individuals are empowered to draw upon phenomenological, practical, social, political, and ecological understandings, interconnected seeing emerges for our dynamic and complex realities (Pimbert p. 277). Pimbert draws upon James Scott’s Seeing Like a State to demonstrate how understanding the daunting complexity of reality requires trusting our experience-based intuition and feeling our way (p. 281). Therefore, it is receptivity to and curiosity toward embodied being that allows these interconnected lenses to emerge. As organizational innovations create sharing spaces which invite and employ the richly sensuous elements of human beings in collective efforts, connection, and action, we see the revitalization of individuals, community, and the wider environment. I will discuss how this process is witnessed in Cuba, the home of my mother’s parents, as the country’s unique and multi-faceted environment has resulted in unparalleled displays and concurrent studies of agro-ecological embodiment. Additionally, I look at Soul Fire Farm in New York as the organization offers a clear path forward to achieve agro-ecological embodiment and reform as a necessary response to the United States unique conditions.

Organizational Innovations

Cuba: The National Association of Small Farmers and Campesino-a-Campesino

Cuba has spearheaded agro-ecological movements for some time now, as the Special Period in the 1990s cut off the country’s access to imported products. As the country could no longer rely on imports of food, or food-inducing instruments, Cuba was forced into developing ecological resilience. This period of resilience and transformation was supported through the adoption of campesino-a-campesino (CAC) grassroots organization. Global CAC movements have been embodiments of agroecology as a pursuit of food system reformation, as peasant farmers share experiential wisdom with one another and forge coalitions. Through observing CAC interchanges, methods of transformative agroecology learning have been identified as a repertoire of action for social movements advancing toward food sovereignty (Anderson et al 2019). Within La Via Campesina (The International Peasants Movement), creating spaces for experiential agroecology interchange among farmer and community networks is vital in the realization of sustainable and just food systems, as individuals realize personal experiences are linked to larger societal problems (Anderson et al 2019). This importance of agro-ecological interchange can be actualized through diálogo de saberes (wisdom dialogues) and horizontal learning which result in combining the practical and the political and building multi-scale social movement networks (Anderson et al 2019). Wisdom dialogues occur when equally valid ways of knowing come into balanced dialogue and foster solidarity, mutual understanding, collective learning, and joint action (Anderson et al 2019). This approach honors the wisdom inherent among farmers, consumers, and research and education institutions and recognizes how they must mutually inform one another. An essential dynamic of these dialogues is that they are non-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian (Stirin 2006). Horizontal learning recognizes the population not as objects of teaching but subjects of their own processes of learning, discovery, and agency and additionally the unique wisdom any individual will bring to the table to help deepen collective understanding (Anderson et al 2019). Through depending on individuals’ perspectives, these perspectives are validated rather than sidelined by mainstream learning approaches. The stengthfulness of this style is further evinced as they foster trust, genuine engagement, confidence, moral support, connection, mutual empowerment, and much more (Anderson et al 2019). One farmer describes how the personal connections and emotional processes evoked in the horizontal learning style of the agroecology movement are about

...the feeling, not just the sharing. It is something more, something very deep and I think that has to be touched upon with cultural things like music, sharing, dreaming” (Anderson et al 2019).

This farmer demonstrates the essentiality of sharing embodied practice and the feelings which emerge as the grounds for agroecological success.

In writing on the Campesino-to-Campesino agroecology movement of The National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP) in Cuba, Rosset and others describe CAC methodology as a horizontal social process which empowers farmers to share new or rediscovered traditional knowledge with other farmers. This mobilizes farmers in active roles of generating and sharing knowledge, in contrast to conventional extensions (Rosset et al 2011).

Farmers in Cuba find this method of horizontal sharing more impactful as demonstrated by their saying “cuando el campesino ve, hace fe” which translates to “when the farmer sees, there is faith” or more popularly “seeing is believing”.

The authors describe CAC as a

participatory method based on local peasant needs, culture, and environmental conditions that unleashes knowledge, enthusiasm and protagonism as a way of discovering, recognizing, taking advantage of, and socializing the rich pool of family and community agricultural knowledge which is linked to their specific historical conditions and identities (Rosset et al 2011).

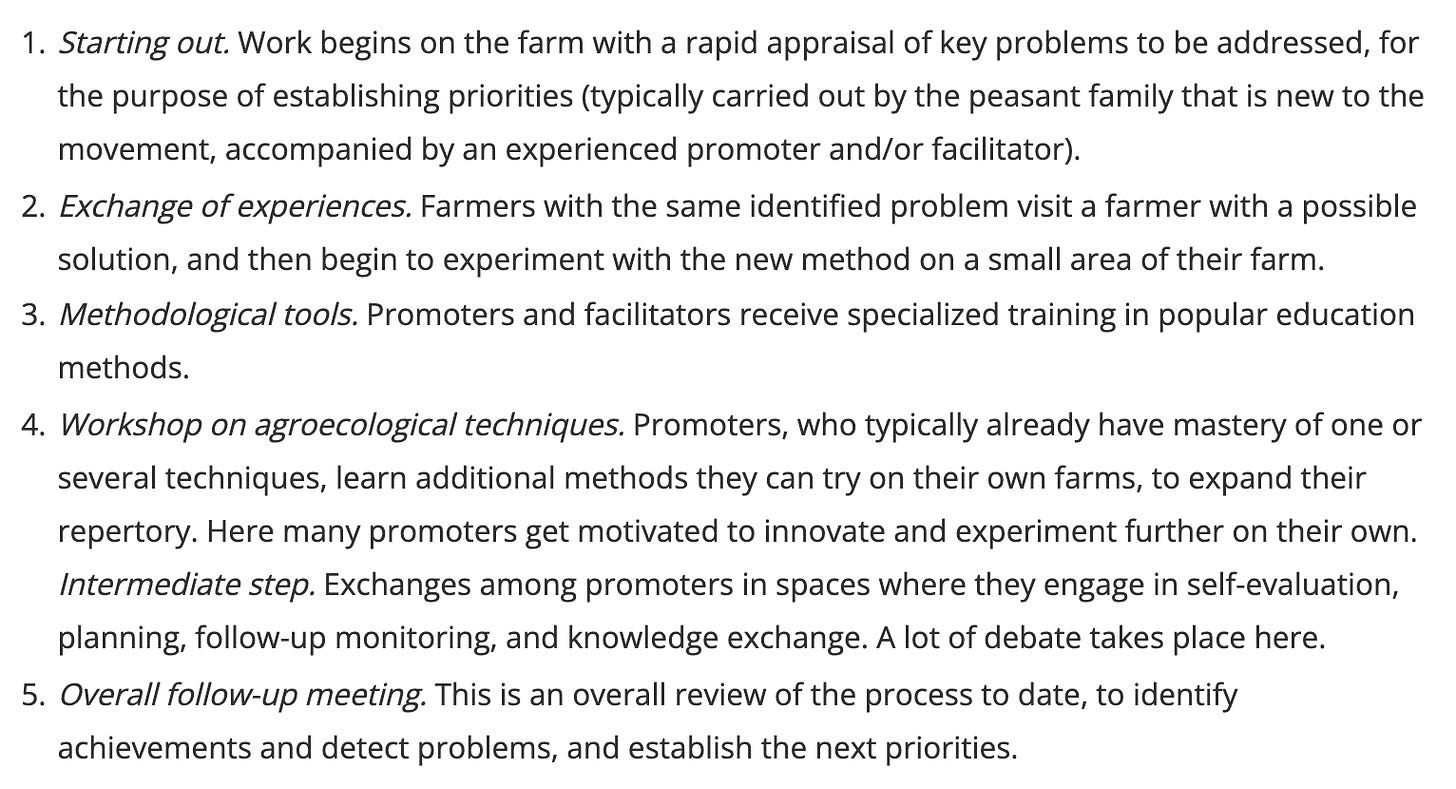

In order to benefit from the vital results alluded to above, the innovations of CAC methodology must be drawn upon. Cuba’s ANAP formally adopted the ‘Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement’ (MACAC) and formalized a five-step process:

These five steps emphasize experiential, place-based learning, farmer to farmer exchange, empowering farmers to insight critical dialogues and learning environments, expanding the developed knowledge, analysis to ensure continued effectiveness and relevance of approaches, and keeping consistency and cycling these processes. When implemented, these processes support sustained exchange among farmers and communities, therefore spreading the scope and impact of the agroecology movement’s reach. For instance, Cuba continues to spearhead the agroecology movement to this day.

Agroecology in Cuba Today

With the adoption of ecological networks, subsequent campesino a campesino movements and agroecology programs helped reach 110,000 peasant families through processes like horizontal exchange, learning, experimentation, and technological innovation occurring between peasant farmers and other actors (Casimiro-Rodríguez 2021). Women have played a fundamental role in these processes whether that be as farmers, community members, professionals, or university professors, but still, female representation is skewed to this day in agricultural work, where women only represent 25% of the sector (Casimiro-Rodríguez 2021).

Leidy Casimiro-Rodríguez, a farmer and agroecologist in Cuba, writes that this occurs as the dominant masculine population in agriculture overvalues productive work, while undermining, and marginalizing, reproductive work and understandings (p. 3). Further, she states that the representation of women in the scientific study of agriculture is severely lacking due to the limited approach of dominant science’s single-minded, ‘objective’ scope. This greatly hinders the visibility of women’s contributions in agroecology, and limits the spreading of diverse visions, knowledge and practices which are critical to the agroecology movement. The roles of women and other marginalized identities must be amplified in order to keep knowledge of medicinal plants, care practices, food production, food safety, fostering and conserving biodiversity, and much more (p. 3). These are the embodied understandings, practices, and contributions which are fundamental for reproductive understanding, food sovereignty, and nutrition education, promoting holistic, sustainable lifestyles.

Women in agriculture have expectations, needs, and demands which have emerged from their particular experiences and realities, and agroecology provides a setting for these women to be empowered to share their wisdoms. Casimiro-Rodríguez calls for action to expand access to food through soft loans, technologies, and infrastructures which reduce working time and increase efficiency, to increase women’s access to productive assets like land and natural resources, improve the livelihoods of peasant families and rural communities to insight self-esteem, dignity, a sense of belonging, and local autonomy (increasing socio-ecological resilience), and to facilitate spaces for agro-ecological transitions (p. 5). She states,

it is necessary to value and promote this empowerment process, the struggle for autonomy and resilience, unlearning and learning in construction from other forms of economy that are based on relationships of solidarity, reciprocity and justice, the practice of care and love for the land and people, spirituality and the fight against all forms of violence (Casimiro-Rodríguez 2021, p. 5).

For these life enhancing states to flourish, marginalized groups must be empowered with the experiences and opportunity to share their knowledge and concurrently reform and bring balance to our food system.

Black Disenfranchisement and Soul Fire Farm

Disenfranchisement is the very basis of the United States’ history, seen as Turtle Island was colonized and Indigenous populations were killed and pillaged of land and livelihoods. The “doctrine of discovery” further took form with the slave trade and slavery, into sharecropping and Jim Crow. Continuing, in 1920 Black farmers made up 14% of the United States farming population, however, due to theft of land and discrimination by the USDA, extension services, banks, etc. and redlining, urban renewal, and mass incarceration, the Black farmer population has declined to 1.4% (Touzeau 2019). Leah Penniman, co-director of Soul Fire Farm, highlights Malcolm X’s quote “Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality”, which offers clear insight into why the cycles of systemic oppression are at play. When minorities have been denied the right to land, and all that goes along with it [everything], it's clear that white farmers, with skewed representation and power, have spawned the oppression of all those denied power [intended or not], whether that be Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC), immigrants, lower socioeconomic classes, LGBTQ+, religious identities, the environment, and so on.

The beginnings of Soul Fire Farm emerged when Leah Penniman’s family directly experienced in-access to fresh, nutritious foods in their neighborhood in the South End of Albany, New York. While this neighborhood is popularly classified by the federal government as a food desert, Penniman is clear that there is nothing natural about structural oppression. Food apartheid is a more accurate term, where 24 million people in the United States face countless barriers due to a human-created system of segregation (Penniman 2018, p. 4). These systems cyclically spawn oppression, which of course is the case considering the long history of disenfranchisement [continuing presently] of marginalized communities. Therefore, Soul Fire Farm has held the intention to empower these diverse communities in the effort of “uprooting racism and seeding sovereignty” to reclaim the land and wellbeing of all.

In Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Farming on the Land, Leah Penniman demonstrates deep understanding and guidance on how to be with the land. Her book proves her to be an expert connection-maker, as she artfully weaves the intricacies of the food (life)-system together. Through and through, her justifications are holistic, offering diverse wisdom on technical farming, land-based spirituality, food medicine and cooking/preserving, movement building, and more. Penniman recognizes the human need for full-engagement, which makes Soul Fire Farm so utterly impactful and exemplary of sensuous revolution. She embodies understanding of land and food being essential to liberation, for the holistic ways they support individuals and community, from sustenance to physiological, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing (Penniman 2018 p. 246). Knowing this, Penniman prioritizes youth empowerment and organizing, defended through her statement, “As stewards of the future, it is incumbent upon us to repair the broken threads in the fabric that weaves together our people and the land” (Penniman 2018, p. 248). Youth programming at Soul Fire Farm aims to interrupt the school-to-prison pipeline and counteract it through the cultivation of meaningful relationships with adults of similar backgrounds, connection with the land, and full respect for their humanity (Penniman 2018 p. 6). Penniman offers a glimpse of how this is put into practice. In the youth program, participants take up basic farming, cooking, and business skills, guided by an important list of principles. These principles are not limited to and include being treated as family and welcomed at the Soul Fire Farm family home and meal table, honoring the participants’ Black, Latinx, and Indigenous ancestors and heros with storytelling, incorporating art, music, rhythm, and creative expression into learning experiences, designing the curriculum around topics and themes which are important to participants and which they want to learn, and more (Penniman pgs. 248-249). Principles like these create democratic learning spaces which honor participants' humanity, experiences, and perspectives. Within these spaces, participants directly embody roles and responsibilities, feeling their interdependent-ness and value. Penniman shares a story of a youth program. She states,

We took our shoes off and placed our bare feet firmly on the warm earth. As we walked past the garlic field, the swallows swooping over the buckwheat flowers, the grandmothers in the ancestor realm whispered their love for us. The most hardened and defended child, who earlier asked, “What’s the point?,” began to weep. His grandmothers reached for him through the earth under his feet and reminded him that there was a point (Penniman 2018, p. 6).

This experiential connection with self, community, and earth offers the relief of understanding realities, and recognizing the necessity for reformation. Penniman goes on,

He and his peers found meaning in tending to the crops that would feed their communities back home, and teaching adults skills they had garnered. They sat in a circle and analyzed the brokenness of the criminal punishment system, compiling necessary policy changes that would be championed by the New York State Prisoner Justice Network. They made bows and arrows in the forest, threw stones in the pond, and allowed themselves some laughter (Penniman 2018, p. 6).

Penniman’s story captures how holistic support for and among youth inspires the strength, confidence, and resiliency to fuel sensuous reformation. Through empowerment, youth have the power and understanding to evince and embody their truth.

Conclusion

Throughout, it has been my hope to demonstrate the struggle between constructions of limited perspectives and practice in society. This paper has perhaps served as my response to the numbness, anxiety, pain, and hate which is manifestly present and all too impactful and powerful in our world. I hope this paper captures that transcendence of those states, when overwhelming, incapacitating, and individualizing, is possible through sensuous embodiment and connection with others. It is this collectivized sensuousness which offers us a source of regenerative healing and action when incorporated into learning spaces and food production practices. Our entire world, present and future, is dependent upon sensuous revolution.

Sources

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. Vintage Books.

Anderson, C. R., Maughan, C., & Pimbert, M. P. (2019). Transformative agroecology learning in Europe: building consciousness, skills and collective capacity for food sovereignty. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(3), 531-547.

Baldwin, J. (1963). The Fire Next Time. New York :Dial Press.

Casimiro-Rodríguez, L. (2021, September 14). Transición Agroecológica, Una Oportunidad para las Mujeres Cubanas. IPS Cuba.

Dostoyevsky, F., & MacAndrew, A. R. (1970). The Brothers Karamazov: A New Translation by Andrew R. MacAndrew: Introductory Essay by Konstantin Mochulsky. Bantam Books.

Houlgate, S. (2005). An Introduction to Hegel. Freedom, Truth and History

Jones, D. (2020). That Thou Art: Aesthetic Soul/Bodies and Self Interbeing in Buddhism,

Phenomenology, and Pragmatism. Eidos. A Journal for Philosophy of Culture, 4(3), 37-47.

Kinloch, V., & Penn, C. (2019). BLACKNESS, LOVE, AND SENSUOUSNESS AS PRAXIS. Sensuous Curriculum: Politics and the Senses in Education, 85.

Morrison, T. (1987). Beloved. New York: Plume, 252.

Penniman, L. (2018). Farming while black: Soul fire farm's practical guide to liberation on the land. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Pimbert, M. (2009). Towards food sovereignty (pp. 1-20). London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Pimbert, M. P. (2017). Democratizing knowledge and ways of knowing for food sovereignty, agroecology, and biocultural diversity. In Food Sovereignty, Agroecology and Biocultural Diversity. Taylor & Francis.

Rosset, P. M., Machín Sosa, B., Roque Jaime, A. M., & Ávila Lozano, D. R. (2011). The Campesino-to-Campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in Cuba: social process methodology in the construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty. The Journal of peasant studies, 38(1), 161-191.

Schiff, R., & Levkoe, C. Z. (2014). From disparate action to collective mobilization: collective action frames and the Canadian food movement. In Occupy the earth: Global environmental movements. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Sitrin, M. (2006). Horizontalism: voices of popular power in Argentina. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Thanissaro, B. (2021, September 16). The clinging to end all clinging. Tricycle. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://tricycle.org/trikedaily/end-clinging/.

Touzeau, L. (2019). "Being Stewards of Land is Our Legacy": Exploring the Lived Experiences of Young Black Farmers. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 8(4), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2019.084.007

Wezel, A., Bellon, S., Doré, T., Francis, C., Vallod, D., & David, C. (2009). Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development, 29(4), 503-515.

Wirzba, N. (2019). Food and faith: A theology of eating. Cambridge University Press.

Wong, Y. L. R. (2018). 9 “Please Call Me by My True Names”. Sharing Breath: Embodied Learning and Decolonization.